Training–Inference Mismatch and Asynchronous Frameworks

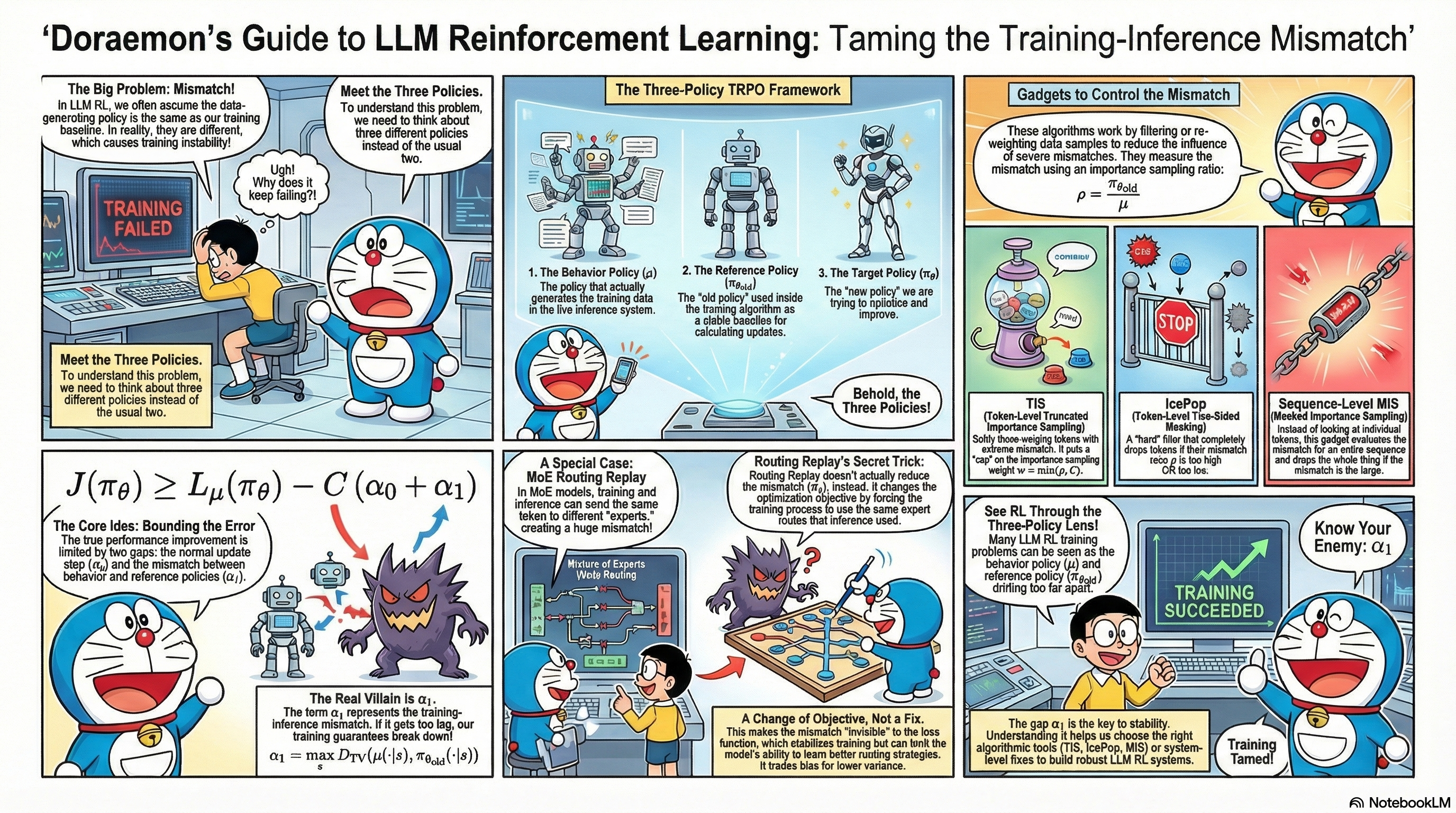

Recently I’ve seen quite a lot of discussion around training–inference mismatch and asynchronous RL frameworks for large language models. My intuition is that many of these seemingly diverse and complicated issues are, in fact, manifestations of a more fundamental tension: a mismatch between the behavior policy and the reference policy.

In this post, I’ll first briefly summarize the related work I’ve come across, and then try to connect them through the lens of “behavior policy vs. reference policy,” as a complementary way to look at the problem.

Throughout the post I’ll use:

-

Behavior policy $\mu$: the policy that actually generates rollouts, i.e., “under which distribution your data are sampled.” In modern LLM RL systems this typically corresponds to the implementation inside the inference engine (vLLM, SGLang, etc.), and under asynchronous frameworks it is often a mixture distribution over multiple worker policies.

-

Reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$: the policy used in the training objective for importance sampling, clipping, or KL constraints — typically the “old policy” in PPO / GRPO.

-

Target policy $\pi_\theta$: the policy we optimize in the training objective, i.e., “what we want the model to become” — typically the “new policy” in PPO / GRPO.

In the classical idealized setup, we usually implicitly assume $\mu = \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$. In real systems, however, asynchronous updates, different inference / training backends, MoE routing fluctuations, and even hardware-level numerical differences cause these two policies to deviate to varying degrees.

Related Work

Below is a rough timeline of the works that left a strong impression on me (this is only a partial and biased subset of the literature I’ve seen):

- Decoupled PPO was among the first to point out that in trust-region policy optimization methods (TRPO and PPO), the “old policy” actually plays two distinct roles:

-

It is used for importance sampling to perform off-policy correction. In this sense, the “old policy” is meant to represent the behavior policy that generated the training data.

-

It is also used to limit the update step size of the new policy. In this sense, the “old policy” acts as a baseline to measure how much the new and old policies differ, i.e., a proximal policy (what I call the reference policy here).

The paper points out that these two roles do not have to be played by the same policy, and proposes the Decoupled PPO objective, which explicitly decouples “who generates the data” from “who defines the trust region” at the level of the optimization objective.

-

-

AReaL focuses on the mismatch between behavior and reference policies under asynchronous training frameworks: rollouts are often generated by stale parameter versions or different workers. The paper adopts a Decoupled-PPO-style objective in the asynchronous setting, explicitly separating the behavior distribution from the reference policy, while still maintaining PPO-like optimization properties in this asynchronous regime.

-

GSPO starts from stability issues of GRPO on long sequences and MoE models. It shows that token-level PPO / GRPO can become highly unstable when MoE expert routing is extremely volatile (especially when routing differs significantly between old and new policies), leading to large variance and training collapse. GSPO proposes a sequence-level PPO-style objective and ratio constraint, using the ratio over entire sequences to control updates. This substantially mitigates training collapse in MoE scenarios caused by routing instability and token-level noise.

-

Your Efficient RL Framework Secretly Brings You Off-Policy RL Training observes that in existing LLM RL frameworks (such as VeRL), the inference stack and the training stack often differ across multiple functional modules (e.g., vLLM vs. FSDP / Megatron kernels and operators). This makes the behavior policy $\mu$ differ from the reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$, so what is assumed to be on-policy training actually becomes off-policy training with nontrivial bias. The article summarizes two existing ways to handle this: PPO-IS and vanilla-IS, and further proposes token-level truncated importance sampling (TIS) to downweight samples with severe training–inference mismatch. The author also wrote two more foundational notes analyzing training–inference mismatch from basic principles: Part I and Part II.

-

Defeating Nondeterminism in LLM Inference points out that the lack of batch-size invariance is a core source of randomness in LLM inference: the same input can yield noticeably different probability distributions under different batch compositions and kernel paths. This means that even when you “nominally” have a single set of parameters, the behavior policy $\mu$ realized in practice can fluctuate with system load and scheduling, further exacerbating training–inference mismatch.

-

Small Leak Can Sink a Great Ship—Boost RL Training on MoE with 𝑰𝒄𝒆𝑷𝒐𝒑! observes that the above mismatch issues are further amplified in MoE models: routing itself is highly sensitive to small perturbations, and stacked with inference / training implementation differences and asynchronous sampling, it is easy to magnify bias and instability. The paper proposes IcePop: at the token level, it computes importance sampling ratios and applies two-sided masking to discard tokens whose ratios are either too large or too small. This removes “very noisy” data from the gradient, stabilizing RL training on MoE models.

-

When Speed Kills Stability: Demystifying RL Collapse from the Training-Inference Mismatch gives a systematic analysis of the causes of training–inference mismatch, including large amounts of out-of-distribution and low-probability content introduced by agent workflows, hardware and kernel-level numerical uncertainty, and how token-level importance sampling can introduce severe bias on long sequences. It further proposes sequence-level masked importance sampling (sequence-level MIS): compute an IS ratio at the sequence level and discard only those sequences whose overall ratio is too large, thereby controlling bias while strongly suppressing training collapse caused by extreme samples. The paper provides reasonably complete theoretical derivations and extensive experimental evidence.

-

Stabilizing MoE Reinforcement Learning by Aligning Training and Inference Routers focuses on the MoE-specific problem of routing inconsistency. The paper finds that even for identical inputs, inference and training can route tokens to different experts due to small differences in operator implementations or parallelism. This “physical-path” mismatch makes the gap between the behavior policy $\mu$ and the reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$ much larger than expected and can easily cause training collapse. To address this, the paper proposes Rollout Routing Replay (R3): during rollout it records, for each token, the actual expert indices selected by the inference router, and during training it replays these routing decisions instead of recomputing them. In effect, R3 forces the training and inference stacks to share the same routing paths in the MoE topology, aligning the two sides at the level of the computation graph.

-

RL 老训崩?训推差异是基石 approaches the problem more from a practical perspective, sharing experience on how to engineer for near training–inference consistency: choosing consistent operators and precision settings, monitoring and constraining the log-prob gap between training and inference, etc. The focus is on framework-level engineering practices that can mitigate training–inference difference at the root.

-

verl Rollout Importance Sampling introduces a Token Veto mechanism in its rollout correction module: it computes token-level importance ratios $\rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})}$, and if any token in a trajectory satisfies $\min_t \rho_t < \tau_{\text{veto}}$, the entire sequence is discarded from training. This “token-level detection, sequence-level veto” design embodies a conservative “one-vote veto” strategy.

- INTELLECT-3 Technical Report adopts a similar rejection sampling strategy in its asynchronous distributed RL training framework. INTELLECT-3 computes token-level importance ratios for each rollout; if any token’s ratio falls below a threshold ($10^{-5}$ in the paper), the entire trajectory is masked.

A Minimally Unified View from a Three-Policy TRPO Perspective

At first glance, the works listed above seem to tackle different aspects:

- Algorithmic level: how to formulate PPO / GRPO objectives, token-level vs. sequence-level, clip vs. mask, etc.

- Systems level: how to align inference and training stacks.

- Model level: how MoE routing amplifies instability, and so on.

However, if we align everything along a single axis — behavior policy vs. reference policy — a large fraction of these issues can be placed in a relatively simple theoretical framework: a three-policy TRPO.

In the next section I’ll unpack this three-policy TRPO in as simple math as I can. You can think of it as “TRPO + triangle inequality” — a very small extension conceptually, but surprisingly handy when analyzing training–inference mismatch in LLM RL:

- On the one hand, it helps us understand what exactly “training–inference mismatch” and “asynchronous training frameworks” are harming within the TRPO view.

- On the other hand, it offers a unifying way to interpret TIS, IcePop, sequence-level MIS, etc. In the view of this post, they can all be seen as different incarnations of Constraint 2 introduced below.

Three Policies

We stick to the notation from above and consider a discounted MDP with discount factor $\gamma \in (0,1)$:

- States $s \in \mathcal{S}$, actions $a \in \mathcal{A}$.

- Policy $\pi(a \mid s)$.

- Discounted state distribution: $$ d_\pi(s) := (1-\gamma)\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t \Pr_\pi(s_t = s). $$

- Return (episodic view): $$ \mathcal{J}(\pi) := \mathbb{E}_\pi\Big[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_t\Big]. $$

- Value / Q / advantage functions: $$ V_\pi(s),\quad Q_\pi(s,a),\quad A_\pi(s,a) := Q_\pi(s,a) - V_\pi(s). $$

It’s worth spelling out that in the three-policy setup we have:

-

Behavior policy $\mu$: the policy that actually generates rollouts. Data $(s,a,r,\dots)$ are sampled from it.

-

Reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$: the “old policy” used in the optimization objective for importance sampling ratios, clipping, or KL constraints.

-

Target policy $\pi_\theta$: the policy we are optimizing in this update.

In the ideal setup we assume $\mu = \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$; in real systems they are often unequal. This is the mathematical shadow of “training–inference mismatch.”

Two-Policy TRPO

If you’re already familiar with TRPO, feel free to skip ahead to the “Three-Policy TRPO” subsection.

All the theoretical guarantees in TRPO are stated with respect to the advantage function of some baseline policy. Since the only advantage we can estimate reliably in practice is $A_\mu$ (data are sampled under $\mu$), we may as well treat $\mu$ as the baseline policy.

A classical result is the Performance Difference Lemma:

For any two policies $\mu$ and $\pi_\theta$, we have

$$ \mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) - \mathcal{J}(\mu) = \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\; \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_{\pi_\theta},\, a\sim\pi_\theta}[A_\mu(s,a)]. $$

The intuition is simple:

- $A_\mu(s,a)$ says: “if I deviate from what $\mu$ would do at state $s$ and instead take action $a$, how much will the long-term return change?”

- Summing that “gain” across all time steps, states, and actions gives the total improvement of the new policy over the behavior policy.

The challenge in TRPO is that we cannot compute

$$ \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_{\pi_\theta}, a\sim\pi_\theta}[A_\mu(s,a)] $$

exactly, because $d_{\pi_\theta}$ is the state distribution of the new policy, under which we do not have samples.

So TRPO introduces a surrogate objective by replacing the state distribution with that of the behavior policy:

$$ L_\mu(\pi_\theta) := \mathcal{J}(\mu) + \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_\mu,\,a\sim \pi_\theta}[A_\mu(s,a)]. $$

Intuitively, $L_\mu$ asks the following question: “Under the states visited by the behavior policy, how good is the new policy if we just let it pick the actions?”

Starting from the Performance Difference Lemma, the difference between the true objective and the surrogate is:

$$ \mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) - L_\mu(\pi_\theta) = \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\; \sum_s \big(d_{\pi_\theta}(s) - d_\mu(s)\big) \,\mathbb{E}_{a\sim\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)}[A_\mu(s,a)]. $$

If we define

$$ \epsilon_\mu := \max_{s,a} |A_\mu(s,a)|, $$

we immediately get the following upper bound:

Lemma 1

$$ |\mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) - L_\mu(\pi_\theta)| \le \frac{\epsilon_\mu}{1-\gamma}\; \|d_{\pi_\theta} - d_\mu\|_1. $$

This reveals the first key quantity:

State distribution shift $\|d_{\pi_\theta} - d_\mu\|_1$, i.e., “how differently the new policy sees the world, compared to the behavior policy.”

We usually do not directly impose constraints on $\|d_{\pi_\theta} - d_\mu\|_1$. Instead, we constrain the per-timestep action distribution difference — via trust regions, KL penalties, clipping, etc.

Define the total variation (TV) distance:

$$ D_{\mathrm{TV}}(p,q) := \frac{1}{2}\|p-q\|_1. $$

Assume there is a constant $\beta$ such that

For all $s$, the TV distance between the behavior and target policies is bounded:

$$ D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s), \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big) \le \beta. $$

Intuitively: in any state, the action distribution of the “new policy” cannot deviate too much from that of the policy that generated the data.

A standard result (provable via coupling) is:

Lemma 2 Under the assumption above,

$$ \|d_{\pi_\theta} - d_\mu\|_1 \le \frac{2\gamma}{1-\gamma}\,\beta. $$

Combining Lemma 1 and Lemma 2, we obtain

$$ |\mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) - L_\mu(\pi_\theta)| \le \frac{\epsilon_\mu}{1-\gamma}\; \frac{2\gamma}{1-\gamma}\,\beta = \frac{2\epsilon_\mu\gamma}{(1-\gamma)^2}\,\beta. $$

This gives a compact two-policy TRPO lower bound (baseline = behavior policy):

Theorem 1 (Two-Policy TRPO)

$$ \mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) \;\ge\; L_\mu(\pi_\theta) \;-\; \frac{2\epsilon_\mu\gamma}{(1-\gamma)^2}\,\beta. $$

This suggests:

- What really matters for the tightness of $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$ as a surrogate for $\mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta)$ is how far the behavior policy $\mu$ and the target policy $\pi_\theta$ drift apart: $$ \beta = \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s), \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big). $$

If you can directly control this $\beta$, you can essentially port TRPO’s monotonic improvement guarantees to the behavior-policy view.

Three-Policy TRPO

In practice, especially in large-scale LLM RL, we often cannot directly control $\beta$ itself.

In most PPO / GRPO / GSPO / RLHF-style frameworks, the actual situation is:

- Rollout data are generated by some behavior policy $\mu$ (some particular parameter version plus system details inside the inference engine).

- During updates, we would like to leverage a reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$ to limit the update of the target policy $\pi_\theta$.

In other words, what we can actually touch and control are two quantities:

-

Reference vs. target: via KL penalties, clipping, etc., we constrain

$$ D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s),\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big). $$

-

Behavior vs. reference: we would like to keep $$ D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s),\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s)\big) $$ small as well — this is where training–inference mismatch and asynchronous execution come in.

This motivates defining two “proxy gaps”:

-

Constraint 1: reference vs. target

$$ \alpha_0 := \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s), \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big); $$

-

Constraint 2: behavior vs. reference $$ \alpha_1 := \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s), \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s)\big). $$

Intuitively:

- $\alpha_0$: how far the new policy is from the “old policy” you are using in the loss — this is the trust-region part.

- $\alpha_1$: how far the reference policy used in training is from the actual behavior policy that generated the data — this is the footprint of training–inference mismatch and asynchrony.

Now we can plug these two quantities back into the TRPO lower bound.

For any state $s$, by the triangle inequality we have

$$ \begin{aligned} D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s),\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big) &\le D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s),\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s)\big) \\ &\quad + D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s),\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big). \end{aligned} $$

Taking the supremum over $s$ gives

$$ \beta := \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s),\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big) \;\le\; \alpha_1 + \alpha_0. $$

Plugging this inequality into the two-policy TRPO bound (Theorem 1), and denoting

$$ C := \frac{2\epsilon_\mu\gamma}{(1-\gamma)^2}, $$

we obtain

$$ \mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) \;\ge\; L_\mu(\pi_\theta) \;-\; C\,\beta \;\ge\; L_\mu(\pi_\theta) \;-\; C\,(\alpha_0 + \alpha_1). $$

This yields a very direct three-policy TRPO lower bound:

Theorem 2 (Three-Policy TRPO) Let

$$ \epsilon_\mu := \max_{s,a} |A_\mu(s,a)|,\quad C := \frac{2\epsilon_\mu\gamma}{(1-\gamma)^2}, $$

and

$$ \alpha_0 := \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s), \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s)\big), \quad \alpha_1 := \max_s D_{\mathrm{TV}}\big(\mu(\cdot\mid s), \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot\mid s)\big). $$

Then for any target policy $\pi_\theta$,

$$ \boxed{ \mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta) \;\ge\; L_\mu(\pi_\theta) \;-\; C\,(\alpha_0 + \alpha_1) } $$

where

$$ L_\mu(\pi_\theta) := \mathcal{J}(\mu) + \frac{1}{1-\gamma} \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_\mu,a\sim\pi_\theta}[A_\mu(s,a)]. $$

The meaning of this bound is quite straightforward:

- The gap between the surrogate objective $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$ and the true performance $\mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta)$ decomposes into two pieces:

- The deviation between reference and target policies, $\alpha_0$.

- The deviation between behavior and reference policies, $\alpha_1$.

As long as both terms are small, optimizing $L_\mu$ is likely to improve $\mathcal{J}$.

How to Control These Two Deviations in Practice?

We can now revisit various practical methods through the lens of Theorem 2:

- Most PPO / GRPO / GSPO-style work focuses on controlling Constraint 1: $\alpha_0$.

- Most TIS / IcePop / MIS-style work, in the view of this post, can be understood as primarily targeting Constraint 2: $\alpha_1$.

In the remainder of this post I will focus on Constraint 2.

The goal of Constraint 2 is: ensure that the data used in training come (effectively) from a behavior policy that is close to the reference policy.

In practice, this usually involves both system-level mechanisms and algorithmic mechanisms (importance sampling).

- System level: keep the behavior policy from drifting too far

-

Asynchronous frameworks: Tag each sample with a policy version, and only use data generated by parameter versions that are close enough to $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$.

-

Training–inference alignment: Use consistent precision, operators, and similar kernel behavior between the training and inference stacks.

These mechanisms act “outside” the algorithm to make $\mu$ closer to $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$, thereby shrinking $\alpha_1$.

-

-

Algorithmic level: sample-wise correction

At the algorithmic level, we no longer attempt to “fix” the entire behavior policy. Instead, we use importance sampling ratios to correct at the sample level: we filter or reweight samples so that the behavior policy is close to the reference policy on the subset of data that actually participates in training, or at least reduce the influence of samples with large mismatch.

Concretely, this gives rise to methods like TIS, IcePop, and MIS, which can be seen as different ways of implementing Constraint 2 at the sample level.

Importance Sampling and Masking: Four Implementations of Constraint 2

In this section I’ll reuse the notation introduced above to write down the objectives of these three methods, focusing only on the design choices related to “behavior vs. reference policy.” Let the token-level PPO / GRPO-style update term be

$$ g_\theta(t) = \min\big(r_t(\theta) A_t,\ \text{clip}(r_t(\theta),1-\epsilon,1+\epsilon) A_t\big), $$

where

$$ r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t\mid s_t)}, \quad (s_t,a_t)\sim\mu,\quad A_t := A_\mu(s_t,a_t). $$

Here:

- $r_t(\theta)$ is the target vs. reference ratio (corresponding to Constraint 1).

- $A_t$ is the advantage estimated from data sampled under the behavior policy.

To connect token-level $(s_t,a_t)$ with sequence-level $(x,y)$ notation, consider the RLHF setting (reinforcement learning from human feedback) for LLMs:

- Prompts are denoted by $x$, and responses by $y = (y_1,\dots,y_{|y|})$.

- Token-level states and actions are defined as $s_t := (x,y_{

- The behavior and reference policies on sequences can then be written as $$ \mu(y\mid x) = \prod_{t=1}^{|y|}\mu(a_t=y_t\mid s_t),\quad \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(y\mid x) = \prod_{t=1}^{|y|}\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t=y_t\mid s_t). $$

To quantify the deviation between reference and behavior policies, we can define the token-level importance ratio:

$$ \rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})} := \frac{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t\mid s_t)}{\mu(a_t\mid s_t)}, $$

and its sequence-level counterpart:

$$ \rho(y\mid x) := \frac{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(y\mid x)}{\mu(y\mid x)} = \prod_{t=1}^{|y|} \rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})}. $$

The difference between TIS, IcePop, and MIS lies in how they use $\rho$ to implement Constraint 2.

1. TIS: Token-Level Truncated Importance Sampling

TIS directly truncates the token-level ratio $\rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})}$; define

$$ \color{blue}{w_t = \min\big(\rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})},\ C_{\text{IS}}\big)}. $$

The update objective becomes

$$ L_{\text{TIS}}(\theta) = - \mathbb{E}_{(s_t,a_t)\sim\mu}\big[\,\color{blue}{w_t}\; g_\theta(t)\big]. $$

- The blue $\color{blue}{w_t}$ is the truncated IS weight: extremely large ratios are capped at a constant $C_{\text{IS}}$.

- From the three-policy TRPO perspective, this is a soft way to downweight tokens where behavior and reference policies differ significantly, effectively reducing their contribution to $\alpha_1$ in the gradient.

2. IcePop: Token-Level Two-Sided Masking in MoE

IcePop also uses $\rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})}$ as a discrepancy measure, but opts for two-sided masking:

$$ \color{blue}{m_t = \mathbf{1}\big[C_{\text{low}} \le \rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})} \le C_{\text{high}}\big]}. $$

The update objective becomes

$$ L_{\text{IcePop}}(\theta) = - \mathbb{E}_{(s_t,a_t)\sim\mu}\big[\,\color{blue}{m_t}\; g_\theta(t)\big]. $$

- The blue $\color{blue}{m_t}$ decides whether a token participates in the update: tokens with ratios that are too large or too small are dropped entirely.

- This is a hard sample selection scheme: only tokens where behavior and reference policies are reasonably aligned (ratios within $[C_{\text{low}}, C_{\text{high}}]$) are kept, implementing a stricter version of Constraint 2 at the token level.

3. Sequence-Level MIS: Masked Importance Sampling Over Entire Sequences

The core operation in sequence-level MIS is to retain only sequences whose sequence-level IS ratio is below a threshold $C$, zeroing out the loss for all other sequences:

$$ \color{blue}{ \rho(y\mid x) \leftarrow \rho(y\mid x)\,\mathbf{1}\{\rho(y\mid x)\le C\} } $$

In a unified loss form, this can be written as

$$ L_{\text{MIS}}(\theta) =-\,\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim\mu} \Big[ \color{blue}{\rho(y\mid x)\,\mathbf{1}\{\rho(y\mid x)\le C\}} \;\cdot\; \sum_{t=1}^{|y|}g_\theta(t) \Big]. $$

In words:

- For sequences with small IS ratios, the full weight $\rho(y\mid x)$ is retained for off-policy correction.

- For sequences whose ratios exceed the threshold $C$, the entire policy loss is masked out (weight set to $0$).

From the three-policy TRPO viewpoint, sequence-level MIS no longer truncates at the token level. Instead, it performs trajectory-level filtering: it drops trajectories where behavior and reference policies diverge too much, and only optimizes on the subset with $\rho(y\mid x)\le C$. This implements Constraint 2 at the sequence level.

4. Worst Token Reject Sampling: Rejecting Entire Sequences Based on the Worst Token

The verl Token Veto mechanism and INTELLECT-3 both adopt a rejection sampling strategy that can be collectively called Worst Token Reject Sampling (WTRS):

-

verl Token Veto: In its rollout correction module, if any token in a trajectory has $\min_t \rho_t < \tau_{\text{veto}}$, the entire sequence is discarded via response*mask. The threshold $\tau*{\text{veto}}$ is user-configurable.

-

INTELLECT-3 Token Masking: In its asynchronous distributed RL framework, if any token’s ratio is below $10^{-5}$, the entire trajectory is masked.

The core operation is identical: if any token in a trajectory has an IS ratio below a threshold $\tau$, the entire sequence is rejected from training. This can be written as:

$$ \color{blue}{ m(y\mid x) = \mathbf{1}\Big\{\min_{t=1}^{|y|} \rho_t^{(\text{ref}\leftarrow\text{beh})} \ge \tau\Big\} } $$

In a unified loss form:

$$ L_{\text{WTRS}}(\theta) =-\,\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim\mu} \Big[ \color{blue}{m(y\mid x)} \;\cdot\; \sum_{t=1}^{|y|}g_\theta(t) \Big]. $$

In words:

- For sequences where all tokens have IS ratios $\ge \tau$: participate in training normally.

- For sequences where any token has an IS ratio $< \tau$: the entire sequence’s policy loss is masked out.

From the three-policy TRPO perspective, WTRS adopts a hybrid “token-level detection, sequence-level veto” strategy: it detects extreme mismatch signals at the token level, and once detected, rejects at the sequence level. This “one-vote veto” design reflects a conservative philosophy — when a trajectory contains a token that “the behavior policy generated but the reference policy would almost never generate,” the credibility of the entire trajectory is called into question, thereby implementing control over Constraint 2 ($\mu$ vs. $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$ deviation) at the trajectory granularity.

MoE Routing Replay: What Does It Actually Do in Three-Policy TRPO?

In MoE (Mixture-of-Experts) models, training–inference mismatch often first appears as routing inconsistency: even with identical parameters, the inference and training stacks may route tokens to different experts because of small differences in operators, parallelism, or numerics. A natural engineering response is routing replay: during rollout (inference), record the actual expert paths, and during training, force the model to reuse these routing decisions.

These methods are often intuitively described as “implementing Constraint 2 and shrinking $\alpha_1$.” From the three-policy TRPO perspective, a more precise statement is:

Routing replay does not tighten the original surrogate objective via a constraint; instead, it rewrites the surrogate objective into one that is conditioned on / replaces the routing. It makes routing mismatch invisible in the loss, but it does not actually shrink the true policy distances $\alpha_0$ or $\alpha_1$.

Below I’ll sketch a minimal abstraction that is sufficient to make this concrete.

Surrogate Objective in MoE: Separating Routing and Token Generation

Abstract an MoE model as a two-stage stochastic decision: “first choose an expert $z$, then generate token $a$ conditioned on that expert.” The target policy can be factorized as

$$ \pi_\theta(a,z\mid s)=\omega_\theta(z\mid s)\,\pi_\theta(a\mid s,z), $$

where:

- $\omega_\theta(z\mid s)$ is the router distribution.

- $\pi_\theta(a\mid s,z)$ is the token distribution conditioned on expert $z$.

In the three-policy TRPO setting, the surrogate objective we actually want to optimize can be written as

$$ L_\mu(\pi_\theta) = \mathcal{J}(\mu) + \frac{1}{1-\gamma} \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_\mu} \bigg[ \sum_z \omega_\theta(z\mid s)\,F_\theta(s,z) \bigg], $$

where I use

$$ F_\theta(s,z) := \sum_a \pi_\theta(a\mid s,z)\,A_\mu(s,a,z) $$

to denote the expert-level aggregation of advantages.

The key point is that in the original $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$, the routing distribution is precisely the current router $\omega_\theta$ that we are updating. In other words, RL on MoE is updating not only the token-generation distribution but also the router itself.

(1) Replaying Behavior-Policy Routing (Behavior-Router Replay / R3-Style)

R3-style methods record, during rollout, the set of experts $M_\mu(s)$ actually selected by the behavior policy on the inference side, and during training force the current policy to route only within this set. This can be written as a “conditional projection” of the routing distribution:

$$ \omega_\theta^{\text{R3}}(z\mid s) := \frac{\omega_\theta(z\mid s)\,\mathbf{1}\{z\in M_\mu(s)\}} {\sum_{z'\in M_\mu(s)}\omega_\theta(z'\mid s)} . $$

The surrogate objective that is actually optimized during training becomes

$$ L_\mu^{\text{R3}}(\pi_\theta) = \mathcal{J}(\mu) + \frac{1}{1-\gamma} \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_\mu} \bigg[ \sum_{z\in M_\mu(s)} \omega_\theta^{\text{R3}}(z\mid s)\,F_\theta(s,z) \bigg]. $$

Compared to the original $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$, R3 does not push $\omega_\theta$ closer to $\omega_{\text{old}}$ or $\omega_\mu$. Instead, it:

- replaces the expectation over $z\sim\omega_\theta$ by a conditional expectation over $z\sim\omega_\theta(\cdot\mid z\in M_\mu(s))$, and

- equivalently, shrinks the feasible routing support to $M_\mu(s)$.

So R3 is optimizing a “behavior-routing-conditioned surrogate objective,” rather than the original $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$. The benefit is substantially reduced variance and improved stability; the cost is that the router’s exploration and update freedom is constrained at every state.

(2) Replaying Reference-Policy Routing (Reference-Router Replay)

Another class of routing-replay schemes instead reuses the reference policy’s router $\omega_{\text{old}}$. This is equivalent to training a hybrid policy

$$ \hat\pi_\theta(a,z\mid s) := \omega_{\text{old}}(z\mid s)\,\pi_\theta(a\mid s,z), $$

with surrogate objective

$$ L_\mu^{\text{ref-replay}}(\pi_\theta) = \mathcal{J}(\mu) + \frac{1}{1-\gamma} \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d_\mu} \bigg[ \sum_z \omega_{\text{old}}(z\mid s)\,F_\theta(s,z) \bigg]. $$

This has the effect that:

- In the surrogate objective, the router is frozen to the old router $\omega_{\text{old}}$, so the “reference vs. target” discrepancy in routing is simply removed from the loss.

- Training becomes insensitive to how far the new router $\omega_\theta$ drifts from $\omega_{\text{old}}$, thereby sidestepping the instabilities caused by routing mismatch.

Again, this is fundamentally a change of objective:

- The deviation $\alpha_0$ in the true policy space is not reduced; it is merely rendered invisible by redefining the surrogate in terms of the old router.

- Learning of the router is effectively frozen or heavily suppressed.

Routing Replay as a Change of Surrogate Objective

Putting these replay variants side by side, they share several properties:

- They optimize not the original $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$, but a surrogate where routing has been conditioned or replaced.

- They do not directly shrink the three-policy TRPO bound’s $\alpha_0$ or $\alpha_1$. Routing mismatch is removed from the loss, but it still exists in the true policy distances.

- In practice they trade bias for variance: replay typically lowers variance and improves stability, but may also limit the router’s ability to learn routing patterns that are optimal for the RL objective.

So, in the three-policy TRPO view, a more accurate characterization is:

Routing replay is best thought of as a rewrite of the surrogate objective, not as a direct implementation of a constraint on $\alpha_0$ or $\alpha_1$.

Conclusion

If I had to compress this post into a single sentence, it would be:

Many issues around “training–inference mismatch” and “asynchronous training” in large-scale LLM RL can be understood, in the TRPO framework, as severely underestimating the deviation between the behavior policy $\mu$ and the reference policy $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$ — i.e., the term $\alpha_1$.

From two policies to three, what we did is conceptually very small:

-

We rewrote the TRPO lower bound from an “old vs. new policy” narrative into a “behavior–reference–target” three-policy relationship.

- We explicitly separated two TV distances:

- Constraint 1: reference vs. target, $\alpha_0$, corresponding to the KL / clip / trust-region style constraints in PPO / GRPO / GSPO.

- Constraint 2: behavior vs. reference, $\alpha_1$, capturing real-world factors like asynchronous frameworks, training–inference mismatch, MoE routing volatility, kernel-level nondeterminism, etc.

- This leads to a simple conclusion: The gap between the surrogate $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$ and the true performance $\mathcal{J}(\pi_\theta)$ scales with $\alpha_0 + \alpha_1$.

Under this lens (which is of course only one of many possible perspectives):

-

Decoupled PPO / AReaL can be viewed as formally acknowledging the existence of three policies and explicitly decoupling the behavior distribution from the reference policy in the objective.

- TIS, IcePop, MIS, and WTRS can be seen as different ways of implementing Constraint 2 using importance sampling truncation / masking:

- TIS: token-level truncation of IS weights to soften the influence of extreme samples.

- IcePop: token-level two-sided masking in MoE to hard-drop tokens with severe mismatch.

- MIS: sequence-level masking to ignore entire trajectories whose behavior–reference mismatch is too large.

- WTRS: token-level detection of extremely small ratios, rejecting the entire trajectory once such a signal is found.

-

Routing replay (whether replaying behavior routing in R3-style schemes or replaying reference routing) is better viewed as changing the surrogate objective rather than directly implementing a constraint: both variants replace the original $L_\mu(\pi_\theta)$ with a routing-conditioned / routing-frozen surrogate, trading off some objective bias and reduced routing learning freedom for lower variance and greater stability, without actually shrinking $\alpha_0$ or $\alpha_1$—they simply make routing mismatch invisible in the loss.

- Engineering advice such as in RL 老训崩?训推差异是基石 and system-level work like Defeating Nondeterminism in LLM Inference can be interpreted as efforts to reduce $\alpha_1$ on the systems and numerical side, so that the assumptions underlying the algorithms do not break too badly.

From this unified perspective, it may also be easier to think about the following practical questions (these are completely open and I don’t have definitive answers):

-

Under what conditions can we still reasonably interpret “LLM RL training” as some approximate form of TRPO / PPO?

- For a concrete RL system, where should we invest more effort:

- tightening $\alpha_0$ (stronger KL control, more stable sequence-level objectives), or

- reducing $\alpha_1$ (better training–inference alignment, more aggressive MIS / TIS / IcePop)?

- In the presence of MoE, asynchronous sampling, and complex agent workflows, how long can we safely pretend that “$\mu \approx \pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$”?

This post is just a very minimal extension of the classic TRPO framework, making the “three policies” explicit and using them to organize some existing work. There are inevitably misunderstandings and omissions. If you also care about how RL training actually behaves in large LLM systems, I’d be very interested to see how your own setup can be abstracted into a relationship between $\mu$, $\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}$, and $\pi_\theta$, and then re-examined through the inequality in Theorem 2. It might give a slightly different intuitive feel for what your system is really optimizing.

@misc{WangZhang2025ThreePolicyTRPO,

author = {Wang, Xihuai and Zhang, Shao},

title = {From Two Policies to Three: Extending TRPO under Behavior-Reference Policy Mismatch in LLM RL},

year = {2025},

month = nov,

day = {15},

url = {https://xihuai18.github.io/reinforcement-learning/2025/11/15/three-policy-en.html},

urldate = {2025-11-23}

}