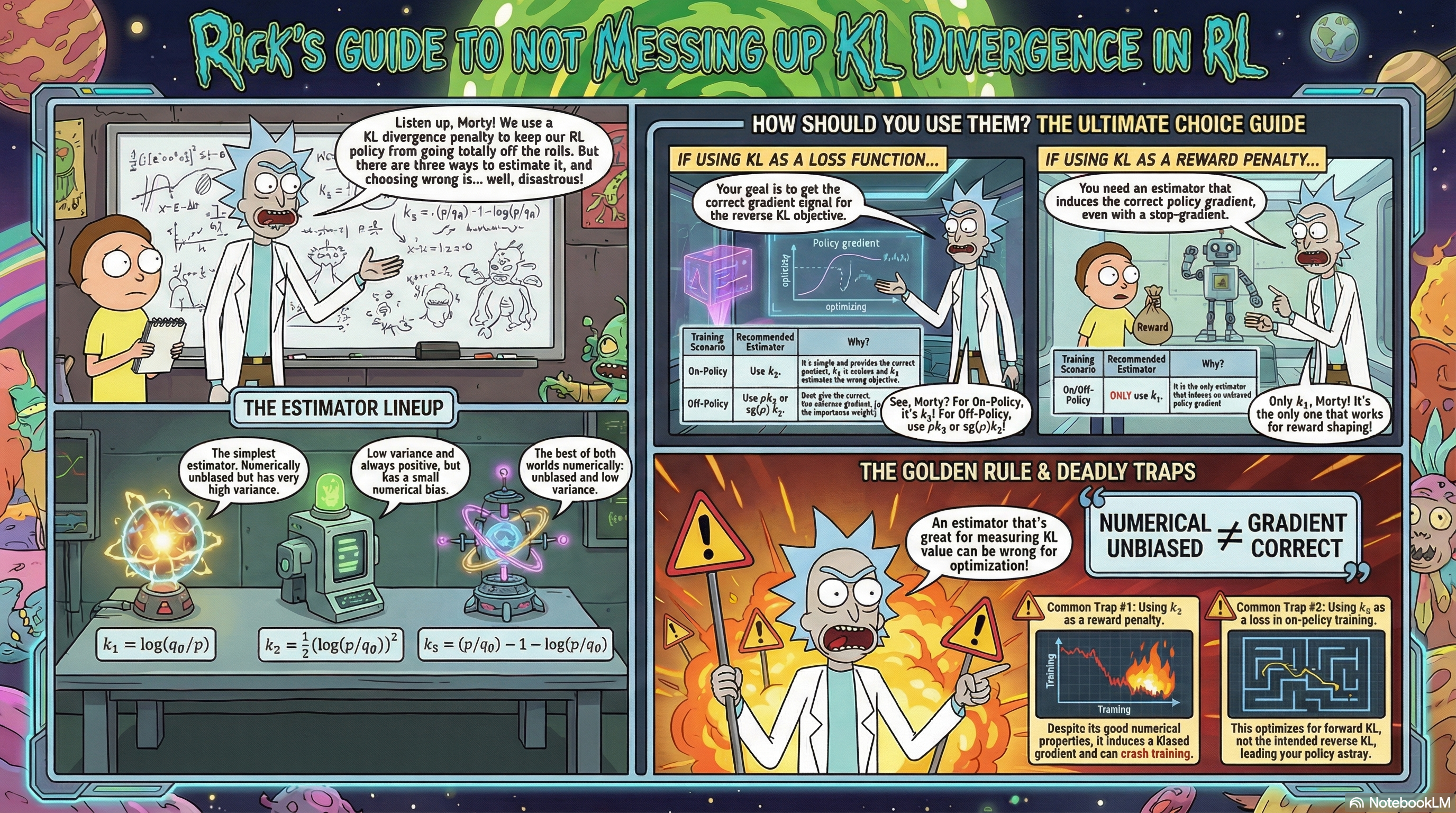

How you approximate KL divergence can make or break training stability. This post analyzes three estimators $k_1, k_2, k_3$ in both on-policy and off-policy settings, and offers practical guidance on choosing them when KL is used as a differentiable loss term versus as a detached reward penalty.

Introduction: The Role of KL Divergence in Reinforcement Learning

In policy optimization (PPO, GRPO, etc.) and alignment training (RLHF/RLAIF), a KL penalty is the primary mechanism for keeping the updated policy from drifting too far from a reference policy, which helps prevent training instability or collapse. In practice, “adding a KL penalty” hides several intertwined design choices: which estimator ($k_1$, $k_2$, $k_3$), which distribution you sample from (on-policy vs. off-policy), and how the KL term enters optimization (as a differentiable loss term vs. as a detached reward penalty). This post makes these choices explicit and clarifies how they relate.

The Distinction Between Forward KL and Reverse KL

Let $q_\theta$ be the current actor policy, $p$ the reference policy. The two directions of KL divergence are:

Reverse KL: $$ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim q_\theta}\left[\log \frac{q_\theta(x)}{p(x)}\right] $$

Forward KL: $$ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}\left[\log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)}\right] $$

Intuition:

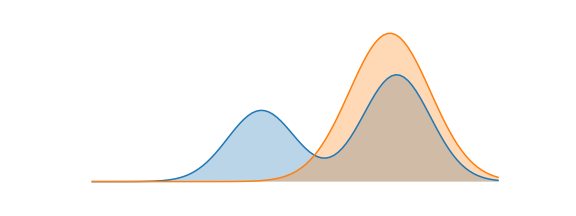

- Reverse KL is mode-seeking: the policy concentrates on high-probability regions of $p$, possibly sacrificing diversity.

- Forward KL is mass-covering: the policy tries to cover the support of $p$.

RLHF typically uses reverse KL because we want the actor not to stray too far from the reference, rather than requiring it to cover every mode.

The Three Core Questions: Who to Sample From, What to Estimate, How to Use

When implementing a KL penalty, it helps to separate three interrelated questions:

- Who to sample from? Do samples come from the current policy $q_\theta$ (on-policy), or from a behavior policy $\mu$ (off-policy)?

- What to estimate? Are we trying to estimate reverse KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p)$ or forward KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta)$?

- How to use it? Is the KL term used as a differentiable loss term, or as a detached reward penalty (stop-gradient)?

Different combinations of these three questions determine which estimator should be used. The goal of this post is to systematically clarify these choices and their interrelationships.

Preliminaries: Notation and Basic Concepts

Before diving into the analysis, let’s unify our notation and derive two fundamental results that will be used repeatedly.

Notation, Sampling Distribution, and True Gradients

Notation:

- $q_\theta$: Current actor policy (parameterized by $\theta$)

- $q$: When unambiguous, we write $q := q_\theta$

- $p$: Reference policy (independent of $\theta$)

- $\mu$: Behavior policy for off-policy sampling (independent of $\theta$)

- $s_\theta(x) = \nabla_\theta \log q_\theta(x)$: Score function

- $\text{sg}(\cdot)$: Stop-gradient operation (

.detach()in code)

A Unified Perspective on Sampling Policies: Introducing the $\rho$ Notation

When analyzing the gradient properties of KL estimators, on-policy and off-policy scenarios may seem to require separate treatment, but we can actually describe them within a unified framework.

Introduce the sampling policy $\mu$, meaning data are drawn from $x \sim \mu$. Define the unified ratio:

$$ \rho(x) := \frac{q_\theta(x)}{\text{sg}(\mu(x))} $$

The key insight is: in both on-policy and off-policy analyses, we treat the sampling policy $\mu$ as a gradient constant (i.e., apply stop-gradient to $\mu$).

- Off-policy ($\mu \neq q_\theta$): $\mu$ is inherently independent of $\theta$, so $\text{sg}(\mu) = \mu$, giving $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\mu}$

- On-policy ($\mu = q_\theta$): Set $\mu = q_\theta$ but stop its gradient, so $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)} \equiv 1$ (numerically always 1), while still having $\nabla_\theta \rho = s_\theta \neq 0$

Implementation note: In the on-policy case, even though $\rho \equiv 1$ numerically, you must explicitly construct $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$ (or equivalently $\rho = \exp(\log q_\theta - \text{sg}(\log q_\theta))$) in the computation graph. If you replace it with the literal constant 1, you cut off the score-function path, causing the derivation to degenerate to the “naive on-policy implementation” described later.

Intuition: The role of $\rho$ is to restore the gradient path for the sampling distribution’s dependence on $\theta$. In the on-policy case, this dependence is precisely why expect-then-differentiate and differentiate-then-expect can disagree, and why explicitly modeling $\rho$ resolves the mismatch.

With this unified notation, we can merge the on-policy and off-policy analyses into a single framework, greatly simplifying the derivations that follow.

Score Function and True KL Gradients

The score function has an important property: $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta] = 0$ (since $\int \nabla_\theta q_\theta dx = \nabla_\theta \int q_\theta dx = \nabla_\theta 1 = 0$).

Using this property, we can derive the true gradients of forward and reverse KL divergences with respect to $\theta$.

Reverse KL Gradient:

$$ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \int q_\theta(x) \log \frac{q_\theta(x)}{p(x)} dx $$

Differentiating with respect to $\theta$ (using the product rule):

$$ \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \int \nabla_\theta q_\theta \cdot \log \frac{q_\theta}{p} dx + \int q_\theta \cdot \nabla_\theta \log \frac{q_\theta}{p} dx $$

Using $\nabla_\theta q_\theta = q_\theta \cdot s_\theta$, $\nabla_\theta \log q_\theta = s_\theta$, and $\nabla_\theta \log p = 0$:

$$ = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \log \frac{q_\theta}{p}\right] + \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \log \frac{q_\theta}{p}\right] $$

Thus:

$$ \boxed{\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \log \frac{q_\theta}{p}\right] = -\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right]} $$

Preview: We will later define $k_1 := -\log\frac{p}{q_\theta}$, so the above can be written concisely as $\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1]$ — this form appears repeatedly in gradient analysis.

Forward KL Gradient:

$$ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = \int p(x) \log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} dx $$

Since $p(x)$ is independent of $\theta$:

$$ \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = \int p(x) \cdot \nabla_\theta \left(-\log q_\theta(x)\right) dx = -\mathbb{E}_p[s_\theta] $$

To estimate this using samples from $q$, apply importance sampling:

$$ -\mathbb{E}_p[s_\theta] = -\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\frac{p}{q_\theta} \cdot s_\theta\right] $$

Using $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta] = 0$, this can be rewritten as:

$$ \boxed{\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\left(1-\frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) \cdot s_\theta\right]} $$

Preview: We will later derive $\nabla_\theta k_3 = (1-\frac{p}{q_\theta}) s_\theta$, so $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla_\theta k_3] = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta)$ (forward KL). This is why directly backpropagating through $k_3$ produces the “wrong” gradient direction when you intend reverse KL.

With these two results, we can later determine which KL’s true gradient each estimator’s gradient expectation corresponds to.

Three Estimators: Definitions and Design Principles

Let $\frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)}$ denote the ratio. John Schulman proposed three single-sample estimators, defined as follows:

The Three Estimators: Definitions and Intuition

$k_1$: The Naive Log-Ratio Estimator

$$ k_1(x) = -\log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} = \log q_\theta(x) - \log p(x) $$

This is the most direct definition: the negative log-ratio. It is unbiased for reverse KL, but it has a major drawback: it can be negative, while KL divergence is always non-negative. This can lead to high variance because positive and negative samples cancel.

$k_2$: The Squared Estimator Based on f-Divergence

$$ k_2(x) = \frac{1}{2}\left(\log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)}\right)^2 $$

Design motivation: $k_1$ can be either positive or negative; squaring yields an estimator where every sample is non-negative, and each sample measures the magnitude of mismatch between $p$ and $q$.

Why is the bias often small? $k_2$ corresponds to an f-divergence with $f(x) = \frac{1}{2}(\log x)^2$. A key fact is that any twice-differentiable f-divergence admits a second-order expansion around $q \approx p$ of the form

$$ D_f\big(p, q_{\theta_0+\Delta\theta}\big) = D_f\big(p, q_{\theta_0}\big) + \frac{f^{\prime\prime}(1)}{2}\, \Delta\theta^T F(\theta_0)\, \Delta\theta + O(\|\Delta\theta\|^3) $$

where $F(\theta_0)$ is the Fisher information matrix at $\theta_0$. KL divergence corresponds to $f(x) = -\log x$, with $f^{\prime\prime}(1) = 1$, while $k_2$ corresponds to $f(x) = \frac{1}{2}(\log x)^2$, which also has $f^{\prime\prime}(1) = 1$. This means that when the two policies are close, $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2]$ and the true KL share the same local second-order curvature, with differences appearing only in higher-order terms.

$k_3$: The Bregman Divergence Estimator via Control Variates

$$ k_3(x) = \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} - 1 - \log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} $$

Design motivation: We want an estimator that is both unbiased and low variance. A standard approach is to add a control variate to $k_1$—a term with zero expectation that (ideally) is negatively correlated with $k_1$.

Note that $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] - 1 = 1 - 1 = 0$, so for any $\lambda$,

$$ k_1 + \lambda\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right) = -\log \frac{p}{q_\theta} + \lambda\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right) $$

remains an unbiased estimator.

Why choose $\lambda = 1$? Since $\log$ is concave, we have $\log x \leq x - 1$, therefore

$$ k_3 = \left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right) - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} \geq 0 $$

It is always non-negative. This ensures every sample contributes “positively” to the estimate, eliminating the cancellation problem of $k_1$.

Geometric intuition: $k_3$ is actually a Bregman divergence. Consider the convex function $\phi(x) = -\log x$, whose tangent at $x=1$ is $y = 1 - x$. The Bregman divergence is defined as the difference between the function value and the tangent value:

$$ \begin{aligned} D_\phi\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta}, 1\right) &= \phi\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) - \phi(1) - \phi'(1)\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right) \\ &= -\log \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 0 - (-1)\left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right) \\ &= \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} \\ &= k_3. \end{aligned} $$

Since a convex function always lies above its tangent, this gap is naturally non-negative. More importantly, as $\frac{p}{q_\theta} \to 1$, the gap shrinks at a second-order rate \left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right)^2, which is the fundamental reason why $k_3$ tends to have lower variance when the policies are close.

Summary: Design Logic Comparison

| Estimator | Definition | Design Principle |

|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | $-\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$ | Naive definition |

| $k_2$ | $\frac{1}{2}\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)^2$ | f-divergence, matches KL to second order |

| $k_3$ | $\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$ | Control variate + Bregman divergence |

With the definitions and design principles in place, we first analyze their behavior as value estimators of KL—specifically, bias and variance.

Value Estimation: Bias and Variance

This section analyzes the properties of the three estimators when estimating KL values. These properties are fundamental in any usage scenario.

Assume we sample from $q_\theta$ to estimate reverse KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p)$:

Unbiasedness Analysis

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_1] &= \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\log \tfrac{q_\theta}{p}\right] = D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) && \textbf{(unbiased)} \\[8pt] \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_3] &= \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] && \\ &= 1 - 1 + D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) && \\ &= D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) && \textbf{(unbiased)} \\[8pt] \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2] &= \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)^2\right] \neq D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) && \textbf{(biased)} \end{aligned} $$

Conclusion: For reverse KL values, $k_1$ and $k_3$ are unbiased estimators, while $k_2$ is biased.

Variance Characteristics

John Schulman’s experiments ($q = \mathcal{N}(0,1)$, $p = \mathcal{N}(0.1,1)$, true KL = 0.005) show:

| Estimator | bias/true | stdev/true |

|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | 0 | 20 |

| $k_2$ | 0.002 | 1.42 |

| $k_3$ | 0 | 1.42 |

When KL is large ($p = \mathcal{N}(1,1)$, true KL = 0.5):

| Estimator | bias/true | stdev/true |

|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | 0 | 2 |

| $k_2$ | 0.25 | 1.73 |

| $k_3$ | 0 | 1.7 |

Intuition:

- $k_1 = -\log \frac{p}{q}$ has a first-order term; when $\frac{p}{q}$ is close to 1 it can fluctuate substantially and can be negative.

- $k_3 = \frac{p}{q} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q}$ is second-order around $\frac{p}{q}=1$ and is always non-negative, which typically yields lower variance when the policies are close.

- In extreme mismatch regimes where $\frac{p}{q}$ can blow up, $k_3$ can inherit large variance from the ratio; in such cases $k_1$ may be more numerically stable.

Summary of Value Estimation

| Estimator | Bias for value | Variance characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | Unbiased | High (can be +/-) |

| $k_2$ | Biased (minimal) | Low (always positive) |

| $k_3$ | Unbiased | Low (always positive) |

From a pure value-estimation perspective, $k_3$ is often the best choice among unbiased estimators due to its lower variance.

Note: To estimate the forward KL value $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_p\left[\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right]$, but only sample from $q_\theta$, use importance sampling $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[\frac{p}{q_\theta} \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right]$.

Two Ways to Use a KL Penalty

Having understood the value properties of these estimators, we need to further clarify: How exactly is the KL penalty applied in reinforcement learning? This choice determines whether we only care about the estimator’s value properties, or must also consider its gradient properties.

Recall the objective for KL-regularized reinforcement learning (where $\tau \sim q_\theta$ denotes the trajectory distribution induced by policy $q_\theta$):

$$ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim q_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^T \gamma^t r(s_t, a_t) \right] - \beta \cdot D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

This mathematical form looks unified, but in actor-critic algorithms (e.g., PPO) it gives rise to two fundamentally different implementation paradigms. They often differ by only a few lines of code, yet correspond to different optimization semantics.

Notation: In this section, we use $\text{KL}_t$ or $\text{KL}(s)$ to generically refer to a token/state-level KL estimator (such as $k_1, k_2, k_3$), with specific definitions from the earlier section “Three Estimators: Definitions and Design Principles”.

As a Loss Term: KL Participates in Backpropagation

actor_loss = -advantage * log_prob + beta * kl # kl participates in gradient

The critic learns only the environment value function; the KL term acts as an explicit regularizer for the actor and participates directly in backpropagation.

As a Reward Penalty: KL Enters Reward Shaping

kl = compute_kl(log_prob_q, log_prob_p).detach()

shaped_reward = reward - beta * kl

KL is treated as part of the reward via reward shaping, and the actor-critic update is performed on the shaped reward. The KL term itself is detached and does not backpropagate.

These two approaches may look like they differ only by a .detach(), but they correspond to different optimization semantics. A detailed comparison appears later in “$k_1$ in Reward vs. Low-Variance KL in Loss: Equivalence and Differences”. Here we first summarize the core distinction:

- KL as a loss term: Requires correct gradients for the KL component, including which objective those gradients correspond to.

- KL as a reward penalty: Requires accurate KL values, and also requires that the induced policy-gradient update matches the intended objective.

Below we analyze estimator gradients under the two usage modes: as a differentiable loss term and as a detached reward penalty.

Gradient Analysis When Used as a Loss Term

When KL serves as a differentiable loss term, the key question is which objective each estimator actually optimizes through its gradient. This is subtle but central in practice.

Leveraging the unified framework introduced earlier, we can merge the on-policy and off-policy analyses into a single derivation. Recall the unified ratio definition:

$$ \rho(x) := \frac{q_\theta(x)}{\text{sg}(\mu(x))} $$

where $\mu$ is the sampling policy. Within this framework:

- On-policy ($\mu = q_\theta$): $\rho \equiv 1$, but $\nabla_\theta \rho = s_\theta$

- Off-policy ($\mu \neq q_\theta$): $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\mu}$, and $\nabla_\theta \rho = \rho \cdot s_\theta$

Basic Gradients of the Three Estimators

First, we compute the gradients of the three estimators themselves (without $\rho$). These results will be used repeatedly in subsequent analysis.

Deriving $\nabla_\theta k_1$:

$$ k_1 = -\log \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} = \log q_\theta(x) - \log p(x) $$

$$ \nabla_\theta k_1 = \nabla_\theta \log q_\theta(x) - \nabla_\theta \log p(x) = s_\theta - 0 = s_\theta $$

Deriving $\nabla_\theta k_2$:

$$ k_2 = \frac{1}{2}\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)^2 $$

By the chain rule:

$$ \begin{aligned} \nabla_\theta k_2 &= \left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) \cdot \nabla_\theta\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) \\ &= \left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) \cdot \nabla_\theta(\log p(x) - \log q_\theta(x)) \\ &= \left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)(-s_\theta) \\ &= - \left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta. \end{aligned} $$

Deriving $\nabla_\theta k_3$:

$$ k_3 = \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} $$

First, compute $\nabla_\theta \frac{p}{q_\theta}$. Since $\frac{p}{q_\theta} = p(x) \cdot q_\theta(x)^{-1}$:

$$ \nabla_\theta \frac{p}{q_\theta} = p(x) \cdot (-1) \cdot q_\theta(x)^{-2} \cdot \nabla_\theta q_\theta(x) = -\frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} \cdot \frac{\nabla_\theta q_\theta(x)}{q_\theta(x)} = -\frac{p}{q_\theta} \cdot s_\theta $$

Then compute $\nabla_\theta \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$:

$$ \nabla_\theta \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} = \frac{q_\theta}{p} \nabla_\theta \frac{p}{q_\theta} = \frac{q_\theta}{p} \cdot \left(-\frac{p}{q_\theta} \cdot s_\theta\right) = -s_\theta $$

Therefore:

$$ \nabla_\theta k_3 = \nabla_\theta \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 0 - \nabla_\theta \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} = -\frac{p}{q_\theta} \cdot s_\theta - (-s_\theta) = \left(1 - \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) \cdot s_\theta $$

Summary: The gradients of the three estimators are:

- $\nabla_\theta k_1 = s_\theta$

- $\nabla_\theta k_2 = -\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta = k_1 \cdot s_\theta$

- $\nabla_\theta k_3 = \left(1 - \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta$

These basic gradients will be used repeatedly in the unified framework analysis that follows.

“Expect-then-Differentiate” vs. “Differentiate-then-Expect”: A Key Pitfall

When analyzing estimator gradients, there is a common pitfall: “expect-then-differentiate” and “differentiate-then-expect” need not agree.

If we treat $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_i]$ as a function of $\theta$ and differentiate analytically (i.e., “expect-then-differentiate”), then because $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_1] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_3] = D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p)$, we have:

$$ \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_1] = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

$$ \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_3] = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

Both yield the reverse-KL gradient. However, when you backpropagate through the sample mean of $k_i$ in code, autograd effectively computes “differentiate-then-expect”, i.e., $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla_\theta k_i]$, which can differ.

The root cause is that the sampling distribution $q_\theta$ depends on $\theta$, so expectation and differentiation cannot be exchanged naively. This is exactly the subtlety in the on-policy case, and why we introduce the unified $\rho$ framework.

Gradient Analysis Under the Unified Framework

Now, we use the $\rho$ framework to uniformly handle on-policy and off-policy scenarios. Consider the loss function form $L = \rho \cdot k$, where $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(\mu)}$.

Key observation: Because $\text{sg}(\mu)$ does not depend on $\theta$, for any differentiable $f_\theta(x)$ we have

$$ \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\mu}[f_\theta(x)] = \mathbb{E}_{\mu}[\nabla_\theta f_\theta(x)] $$

This means that under the $\rho$ framework, “expect-then-differentiate” and “differentiate-then-expect” are always equivalent, whether on-policy or off-policy.

Note: The expectation here is $\mathbb{E}_\mu[\cdot]$ over a fixed sampling distribution $\mu$. We route “distribution dependence on $\theta$” through $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(\mu)}$. This does not mean you can always exchange expectation and differentiation under $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\cdot]$.

Gradient Derivations for the Three Estimators Under the Unified Framework

Using $\nabla_\theta \rho = \rho \cdot s_\theta$ (since $\rho = q_\theta / \text{sg}(\mu)$), combined with the previously derived $\nabla_\theta k_i$, applying the product rule:

$\nabla_\theta(\rho k_1)$:

$$ \nabla_\theta(\rho k_1) = (\nabla_\theta \rho) k_1 + \rho (\nabla_\theta k_1) = \rho s_\theta k_1 + \rho s_\theta = \rho s_\theta (k_1 + 1) $$

$\nabla_\theta(\rho k_2)$:

$$ \nabla_\theta(\rho k_2) = \rho s_\theta k_2 + \rho \left(-\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta = \rho s_\theta \left(k_2 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) = \rho s_\theta (k_2 + k_1) $$

$\nabla_\theta(\text{sg}(\rho) k_2)$ (applying stop-gradient to $\rho$):

$$ \nabla_\theta(\text{sg}(\rho) k_2) = \text{sg}(\rho) \cdot \nabla_\theta k_2 = \rho \cdot \left(-\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta = \rho s_\theta k_1 $$

$\nabla_\theta(\rho k_3)$:

$$ \nabla_\theta(\rho k_3) = \rho s_\theta k_3 + \rho \left(1-\frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) s_\theta = \rho s_\theta \left(k_3 + 1 - \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) $$

Substituting $k_3 = \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$:

$$ k_3 + 1 - \frac{p}{q_\theta} = \left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right) + 1 - \frac{p}{q_\theta} = -\log \frac{p}{q_\theta} = k_1 $$

Thus we obtain a key simplification:

$$ \boxed{\nabla_\theta(\rho k_3) = \rho s_\theta k_1} $$

Gradient Expectations and Optimization Objectives

Using $\mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho \cdot f] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[f]$ and $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta] = 0$:

$\mathbb{E}_\mu[\nabla_\theta(\rho k_1)]$:

$$ \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta (k_1 + 1)] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_1] + \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta]}_{=0} = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) \quad \checkmark $$

$\mathbb{E}_\mu[\nabla_\theta(\rho k_2)]$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta (k_2 + k_1)] &= \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_2] + \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_1] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_2] + \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla_\theta k_2] && \text{(since } \nabla_\theta k_2 = k_1 s_\theta \text{)} \\ &= \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2] && \text{(Leibniz rule)} \end{aligned} $$

In other words, the gradient expectation of $\rho k_2$ corresponds to “minimizing $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2]$” (an f-divergence with second-order behavior matching KL), not the true gradient of reverse KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta\|p)$; therefore, when the goal is reverse KL, avoid using $\rho k_2$.

$\mathbb{E}_\mu[\nabla_\theta(\text{sg}(\rho) k_2)]$:

$$ \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta k_1] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_1] = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) \quad \checkmark $$

$\mathbb{E}_\mu[\nabla_\theta(\rho k_3)]$:

$$ \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta k_1] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta k_1] = \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) \quad \checkmark $$

Gradient Equivalence: Which Methods Produce Identical Gradient Random Variables

From the above derivations, we discover a key fact:

$\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ and $\rho k_3$ have identical gradients: $\nabla_\theta(\text{sg}(\rho) k_2) = \nabla_\theta(\rho k_3) = \rho s_\theta k_1$

This means they are equal not only in expectation, but as random variables: same mean, variance, and higher moments.

Summary Table:

| Loss Form | Gradient Random Variable | Expected Gradient | Optimization Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\rho k_1$ | $\rho s_\theta (k_1+1)$ | $\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL ✓ |

| $\rho k_2$ | $\rho s_\theta (k_2 + k_1)$ | $\nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2]$ | f-divergence (not reverse KL) ✗ |

| $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ | $\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL ✓ |

| $\rho k_3$ | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ | $\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL ✓ |

A Unified View of On-Policy and Off-Policy

We can now revisit the relationship between on-policy and off-policy settings through the unified framework.

On-policy ($\mu = q_\theta$):

- $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)} \equiv 1$ (numerically always 1)

- $\rho k_1 = k_1$, $\rho k_2 = k_2$, $\rho k_3 = k_3$

- But the gradients differ, because $\nabla_\theta \rho = s_\theta \neq 0$.

This explains why naive direct backpropagation (i.e., without explicitly constructing $\rho$) fails when using $k_1$ or $k_3$ as the KL loss term in the on-policy case:

- Directly using $k_1$ (without $\rho$): $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_1] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta] = 0$, so the KL term is ineffective.

- Directly using $k_3$ (without $\rho$): $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_3] = \nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta)$ (forward KL), i.e., the wrong direction for reverse-KL regularization.

- Directly using $k_2$: $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_2] = \nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p)$ (reverse KL), which makes it the only correct choice under the naive implementation.

If you explicitly construct $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$, then:

- Usable: $\rho k_1$ (higher variance), $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ (recommended), and $\rho k_3$ (recommended) all yield reverse-KL gradients.

- Not usable: $\rho k_2$ (where $\rho$ participates in the gradient) optimizes an f-divergence rather than the reverse KL.

Off-policy ($\mu \neq q_\theta$):

- $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\mu}$ (standard importance weight)

- Usable: $\rho k_1$ (higher variance), $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ (recommended), and $\rho k_3$ (recommended) all yield reverse-KL gradients.

- Not usable: $\rho k_2$ (where $\rho$ participates in the gradient) optimizes an f-divergence rather than the reverse KL.

Key insight: The reason $k_2$ works directly in the on-policy case is that its gradient $-\log\frac{p}{q_\theta} \cdot s_\theta = k_1 \cdot s_\theta$ happens to match $\rho s_\theta k_1$ (when $\rho \equiv 1$). This is a special case, not a general rule.

For an in-depth analysis of off-policy scenarios in large language models, refer to my previous blog post: From Two-Policy to Three-Policy: TRPO Extension Under Behavior-Reference Mismatch in LLM RL.

Variance Analysis

Earlier we saw that three choices give unbiased gradients for reverse KL: $\rho k_1$, $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$, $\rho k_3$. Their gradient random variables are (note that $s_\theta$ is a vector, so the gradient is also a vector):

$$ g_1(x) = \rho(x) s_\theta(x) (k_1(x) + 1), \quad g_\star(x) = \rho(x) s_\theta(x) k_1(x) $$

where $g_\star$ corresponds to both $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ and $\rho k_3$ (they are identical).

To avoid ambiguity in “variance of a vector gradient”, we compare the projection variance in any direction: take any unit vector $u$, and define scalar random variables

$$ g_1^{(u)} := u^\top g_1, \quad g_\star^{(u)} := u^\top g_\star. $$

Let $A_u(x) := \rho(x)\, u^\top s_\theta(x)$, $B(x) := k_1(x)$, then

$$ g_1^{(u)} = A_u(B+1), \quad g_\star^{(u)} = A_u B. $$

Both have the same expectation, and the variance difference in any direction is

$$ \boxed{ \mathrm{Var}_\mu\big(g_1^{(u)}\big) - \mathrm{Var}_\mu\big(g_\star^{(u)}\big) = \mathbb{E}_\mu\big[A_u(x)^2 \big(2B(x)+1\big)\big] = \mathbb{E}_\mu\Big[\rho(x)^2\,\big(u^\top s_\theta(x)\big)^2\,\big(2k_1(x)+1\big)\Big]. } $$

(You can also understand this as comparing variance for each coordinate component separately; the conclusion is consistent with intuitive magnitude estimates.)

In the typical KL penalty regime ($q_\theta \approx p \approx \mu$), setting $\frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} = 1 + \varepsilon(x)$, $|\varepsilon| \ll 1$:

- $k_1 = -\log \frac{p}{q_\theta} \approx -\varepsilon$

- $2k_1 + 1 \approx 1 - 2\varepsilon$, with the leading term being a positive $O(1)$ constant

Therefore $\mathrm{Var}_\mu(g_1) > \mathrm{Var}_\mu(g_\star)$.

Core intuitive understanding:

- $g_1 = \rho s_\theta (k_1 + 1)$ contains a zero-mean noise term of magnitude $O(1)$: $\rho s_\theta$

- $g_\star = \rho s_\theta k_1$ has eliminated this constant noise term, leaving only first-order terms proportional to $\varepsilon$

Variance Comparison Table:

| Estimator | Gradient Random Variable | Coefficient Magnitude ($\frac{p}{q_\theta}\approx1$) | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\rho k_1$ | $\rho s_\theta (k_1+1)$ | $O(1)$ | High |

| $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ | $O(\varepsilon)$ | Low |

| $\rho k_3$ | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ | $O(\varepsilon)$ | Low |

Conclusion: $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ and $\rho k_3$ are equivalent at the gradient level (the same random variable). In contrast, $\rho k_1$ contains an additional zero-mean constant term, which leads to substantially higher variance in the typical small-KL regime.

Practical recommendation: For optimizing reverse KL, prefer $\rho k_3$ or $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ (both have equivalent gradients and low variance); $\rho k_1$ is unbiased but has higher variance, and can serve as a fallback with clipping/regularization.

Warning (extreme off-policy mismatch):

When $\mu$ differs greatly from $q_\theta$ — for example, when $\mu$ has almost no samples in high-density regions of $q_\theta$, or when $\rho = q_\theta / \mu$ explodes in the tails — any $\rho$-based method will suffer from severe variance issues. In such cases, the advantage of $\rho k_3$ (or $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$) over $\rho k_1$ is no longer theoretically guaranteed, and strategies like clipping and regularization must be combined.

However, in RL practice we typically control KL constraints and limit the degree of off-policy sampling (e.g., using a nearby policy $\mu = q_{\theta_\text{old}}$). In this common regime, we can say with confidence:

If you’ve decided to use importance sampling to optimize reverse KL, we recommend using $\rho k_3$ or $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ (both have equivalent gradients and low variance); in comparison, $\rho k_1$ has higher variance.

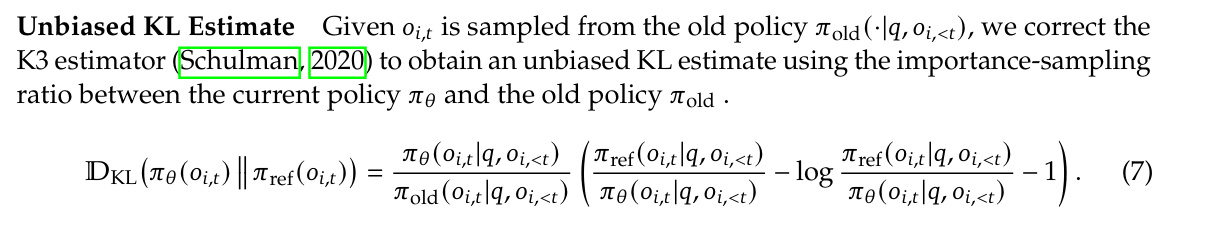

This is why the DeepSeek v3.2 technical report uses $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_3$ as an off-policy KL penalty estimator.

Comprehensive Gradient Analysis Summary

Combining the above analysis, the following table summarizes the gradient expectations and corresponding optimization objectives for each estimator under the unified framework:

| Sampling Type | Loss | Expected $\nabla_\theta$ Loss | Optimization Objective | Usable for Reverse KL? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on/off-policy | $\rho k_1$ | $\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL | ✓ (higher variance) |

| on/off-policy | $\rho k_2$ | $\nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[k_2]$ | f-divergence (not reverse KL) | ✗ |

| on/off-policy | $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ | $\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL | ✓ (recommended, low variance) |

| on/off-policy | $\rho k_3$ | $\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q \| p)$ | Reverse KL | ✓ (recommended, low variance) |

where $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(\mu)}$. When on-policy ($\mu = q_\theta$), $\rho \equiv 1$.

It must be emphasized: the conclusions in the table above apply to the unified framework where “loss is written as $L=\rho\,k$ and $\rho$ retains its gradient path in the computation graph”. In the on-policy case, although $\rho \equiv 1$ numerically, since $\rho=\frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$, we still have $\nabla_\theta\rho=s_\theta\neq 0$, so $\rho k$ and “directly backpropagating through the sample mean of $k$” are not equivalent in terms of gradients.

If you use the naive on-policy implementation (i.e., after sampling from $q_\theta$, treat $\{k_i(x)\}$ as ordinary scalars and directly backpropagate through their sample mean; without explicitly constructing $\rho=\frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$ to restore the score-function path), then it degenerates to:

- Directly using $k_1$: $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_1]=0$ (ineffective)

- Directly using $k_2$: $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_2]=\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta\|p)$ (reverse KL) ✓

- Directly using $k_3$: $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[\nabla k_3]=\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p\|q_\theta)$ (forward KL) ✗

Key Conclusions:

- On-policy optimization of reverse KL (naive direct backprop implementation): The only correct choice is $k_2$

- Off-policy optimization of reverse KL: Three correct options:

- $\rho k_1$: Unbiased but higher variance

- $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$: Unbiased, gradient identical to $\rho k_3$

- $\rho k_3$: Unbiased and lower variance (equivalent to the above, both recommended)

- $\rho k_2$ (weight participates in gradient) fails: This is an easily overlooked pitfall

Gradient Analysis When Used as a Reward Penalty

Having analyzed the gradient properties of the three estimators when used as loss, one might naturally think: since both $k_1$ and $k_3$ are unbiased for reverse KL value (see the “Value Estimation” section), using either of them (with stop-gradient) as a reward penalty should work fine.

But this conclusion is incomplete.

The issue is that when KL is used as a reward penalty, the KL term is detached, but it still influences the policy update through the advantage. Therefore, to decide whether an estimator is appropriate “in reward”, you must consider not only value bias, but whether the induced policy gradient is correct.

The True KL-Regularized Policy Gradient

Consider the KL-regularized reinforcement learning objective:

$$ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[R] - \beta \cdot D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

Its true gradient is:

$$ \nabla_\theta J = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot R] - \beta \cdot \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

Using the result from the “Preliminaries” section, the reverse KL gradient is:

$$ \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \left(-\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)\right] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1] $$

Therefore, the true KL-regularized policy gradient is:

$$ \nabla_\theta J = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \left(R - \beta \cdot k_1\right)\right] $$

Gradient Form When Using Estimator $\hat{k}$

When we use some estimator $\hat{k}$ (with stop-gradient) as a reward penalty, the shaped reward is $\tilde{R} = R - \beta \cdot \text{sg}(\hat{k})$, and the policy gradient becomes:

$$ \nabla_\theta \tilde{J} = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot (R - \beta \cdot \hat{k})\right] $$

Unbiasedness condition: $\nabla_\theta \tilde{J} = \nabla_\theta J$ if and only if

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot \hat{k}] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1] $$

Using $k_1$ as Penalty: Gradient Unbiased

When $\hat{k} = k_1$, the condition is automatically satisfied:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1] \quad \checkmark $$

Therefore, when $k_1$ is used as a reward penalty, the induced policy gradient is unbiased.

Using $k_3$ as Penalty: Gradient Biased

When $\hat{k} = k_3 = \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_3] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right)\right] + \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \left(-\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)\right] $$

The second term is exactly $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1]$. The problem lies in the first term:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \left(\frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1\right)\right] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] - \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta]}_{=0} = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] $$

This can be rewritten as:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] = \int q_\theta(x) \cdot \nabla_\theta \log q_\theta(x) \cdot \frac{p(x)}{q_\theta(x)} dx = \int p(x) \cdot \nabla_\theta \log q_\theta(x) dx = \mathbb{E}_p[s_\theta] $$

Using the forward KL gradient formula $\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) = -\mathbb{E}_p[s_\theta]$, we have:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}\left[s_\theta \cdot \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right] = -\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta) $$

Therefore:

$$ \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_3] = \underbrace{-\nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta)}_{\text{bias term}} + \nabla_\theta D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p) $$

When $k_3$ is used as a reward penalty, the gradient is biased, with the bias term equal to the negative of the forward KL gradient.

Interpretation of the bias: Using $k_3$ as a reward penalty is equivalent to optimizing a mixed objective that you likely do not intend:

- Penalizing reverse KL (hoping policy doesn’t deviate from reference)

- But also wrongly encouraging forward KL to increase (hoping reference doesn’t cover policy)

These two directions can conflict and destabilize optimization.

Empirical evidence: Shah et al. (2025) report that in on-policy RL fine-tuning of LLMs:

- $k_1$ in reward: Training is stable

- $k_3$ in reward: Training collapses

This is consistent with the theoretical analysis above.

Off-Policy Scenario Conclusions

The above analysis assumes on-policy sampling. Does the conclusion change in off-policy scenarios?

Let samples come from behavior policy $\mu$, using importance-weighted policy gradient:

$$ \nabla_\theta \tilde{J} = \mathbb{E}_\mu\left[\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} \cdot s_\theta \cdot (R - \beta \cdot k)\right] $$

Using $\mathbb{E}_\mu[\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} \cdot f] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[f]$, this equals:

$$ = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot R] - \beta \cdot \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k] $$

The unbiasedness condition remains $\mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k] = \mathbb{E}_{q_\theta}[s_\theta \cdot k_1]$, exactly the same as on-policy.

Key insight: In an off-policy policy-gradient estimator, the importance weight $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu}$ multiplies the entire policy-gradient term. There is no need to additionally importance-weight the KL scalar inside the shaped reward. Therefore:

- Shaped reward keeps its original form: $\tilde{R} = R - \beta \cdot k_1$ (not $R - \beta \cdot \frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_1$)

- Under the stop-gradient reward shaping ($\tilde{R}=R-\beta\,\text{sg}(k)$) with the reverse-KL regularization setting discussed in this post, the conclusion is the same as in the on-policy case: use $k_1$, not $k_3$.

Key Finding: Only $k_1$ Is Suitable as a Reward Penalty

| Estimator | Value unbiased? | Gradient unbiased when used as reward penalty? | Actual performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | ✓ | ✓ | Stable |

| $k_3$ | ✓ | ✗ | Collapses |

Core lesson: “Value unbiasedness” and “gradient correctness” are independent axes. For the reward-penalty setup discussed here (stop-gradient reward shaping with reverse-KL regularization, on-policy or off-policy), only $k_1$ yields the correct induced policy gradient. Even though $k_3$ is value-unbiased and often lower variance, using it as a reward penalty introduces a biased update and may trigger collapse.

At this point, an apparent tension may arise:

- In reward penalty we emphasize “only use $k_1$”;

- But in the earlier loss-term backpropagation discussion (especially off-policy), we recommend using $\rho k_3$ or $\text{sg}(\rho)k_2$ for lower-variance reverse-KL gradients.

The next section explains why these are not contradictory: for the KL regularization term’s contribution to the policy-gradient update, the two implementations can be sample-wise equivalent. The practical differences arise mainly from whether the KL term enters the advantage/baseline and from the resulting credit-assignment pathway.

$k_1$ in Reward vs. Low-Variance KL in Loss: Equivalence and Differences

Having separately analyzed KL as Loss and as Reward, a natural question arises: In what sense are these two approaches equivalent, and how do they differ? This section explores this question in depth, with particular focus on LLM RL practice.

Sample-Level Equivalence of the KL Gradient Term

This section compares only the policy-gradient contribution from KL regularization, written as the ascent direction $\nabla_\theta J$ (minimizing a loss is just a global sign flip). We also keep the unified notation: samples come from $x \sim \mu$, and the importance weight $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(\mu)}$ multiplies the policy-gradient estimator.

Recall the key conclusions from earlier:

KL as Loss (low-variance choice): We proved earlier that when using $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ or $\rho k_3$ as the regularization term, the gradient random variable simplifies to

$$ \nabla_\theta(\text{sg}(\rho) k_2) = \nabla_\theta(\rho k_3) = \rho s_\theta k_1 $$

KL as Reward ($k_1$ in reward): The shaped reward is $\tilde{R} = R - \beta \cdot k_1$ (applying stop-gradient to $k_1$ just avoids “KL directly backpropagating” in implementation, without changing its numerical value as a penalty). In the “policy gradient term”, the KL penalty contributes

$$ \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta \cdot (-\beta k_1)] = -\beta \cdot \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta k_1] $$

Key finding: The KL gradient terms from both approaches are identical at the sample level.

In other words, ignoring the specific construction details of baseline/advantage:

- “Writing KL into loss with low-variance implementation ($\text{sg}(\rho)k_2$ or $\rho k_3$)”

- and “Writing KL into reward with $k_1$ (stop-gradient shaped reward)”

can exert exactly the same KL regularization “force” on policy updates.

Specifically, if we only look at the gradient term contributed by KL penalty when “maximizing $J$” (the penalty term carries a negative sign in $J$, so the ascent direction naturally carries $-\beta$):

- KL in Loss (low-variance implementation): $-\beta \cdot \rho s_\theta k_1$

- KL in Reward ($k_1$ in reward): $\rho s_\theta \cdot (-\beta k_1) = -\beta \cdot \rho s_\theta k_1$

They are the same random variable, not just equal in expectation.

Where the Two Implementations Still Differ

Although the KL gradient terms are sample-level equivalent, the overall update semantics of the two approaches still differ. The differences mainly manifest in the following aspects:

1. Whether KL Enters Advantage/Baseline

KL as Loss (equivalent to maximizing $J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}[R] - \beta\,\mathrm{KL}$, but implementing the KL term as an independent, controllable “explicit force”):

$$ \nabla_\theta J_{\text{loss-impl}} = \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta A_{\text{env}}]}_{\text{RL ascent direction}} + \underbrace{(-\beta) \cdot \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta k_1]}_{\text{independent KL penalty ascent direction}} $$

KL is an independent regularization term, completely decoupled from advantage. The magnitude of the KL gradient depends only on $k_1$ itself, unaffected by critic quality or baseline choice.

KL as Reward:

$$ \nabla_\theta J_{\text{reward-impl}} = \mathbb{E}_\mu[\rho s_\theta \tilde{A}], \quad \tilde{A} \text{ based on } (R - \beta \cdot k_1) $$

KL enters advantage computation through shaped reward and gets processed by the baseline. This means:

- KL’s influence is modulated by how advantage is constructed

- If using a value function baseline, KL’s influence is partially absorbed

From an implementation perspective, the difference can be understood as: the Loss approach estimates “environment return” and “KL regularization” separately; the Reward approach treats KL as part of the return, so it follows all the processing you do to returns (baseline, normalization, clipping, etc.).

2. Credit Assignment: Explicit Regularization vs. Shaped-Reward Coupling

KL as Loss: Each token/state’s KL gradient is local, directly affecting the update at that position.

KL as Reward: The KL penalty is folded into the return/advantage computation and can influence earlier decisions depending on how returns are propagated.

3. Reward-Centered KL: Impact on Gradient Unbiasedness

In LLM RL (such as GRPO, PPO for LLM), a common advantage computation is $A = r - \text{mean}(r)$. When KL is used as a reward penalty, whether to include KL in the mean affects gradient unbiasedness.

Let samples be $x_1, \dots, x_n \overset{iid}{\sim} q_\theta$, denote $g_i = \nabla_\theta \log q_\theta(x_i)$, and use $\mathrm{kl}_i$ for the KL penalty scalar of the $i$-th sample, $\bar{\mathrm{kl}} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_j \mathrm{kl}_j$.

No centering ($-\beta\,\mathrm{kl}_i$): The expected KL gradient term is

$$ -\beta \mathbb{E}[g_i\,\mathrm{kl}_i] = -\beta \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}[\mathrm{KL}] $$

This is an unbiased gradient of $-\beta \mathbb{E}[\mathrm{KL}]$.

Same-batch mean centering ($-\beta(\mathrm{kl}_i - \bar{\mathrm{kl}})$, including self): Since $\bar{\mathrm{kl}}$ depends on all samples (including $x_i$ itself), the expected gradient becomes

$$ -\beta \left(1 - \frac{1}{n}\right) \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}[\mathrm{KL}] $$

The KL regularization gradient is shrunk by $\frac{1}{n}$, equivalent to a smaller effective $\beta$. This is not strictly unbiased.

Leave-one-out centering ($-\beta(\mathrm{kl}_i - \bar{\mathrm{kl}}_{-i})$): If we use $\bar{\mathrm{kl}}_{-i} = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{j \neq i} \mathrm{kl}_j$ instead, then $\bar{\mathrm{kl}}_{-i}$ is independent of $g_i$, giving $\mathbb{E}[g_i \bar{\mathrm{kl}}_{-i}] = 0$, therefore

$$ -\beta \mathbb{E}[g_i (\mathrm{kl}_i - \bar{\mathrm{kl}}_{-i})] = -\beta \nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}[\mathrm{KL}] $$

This remains an unbiased gradient, while enjoying variance reduction from centering.

Conclusion: Same-batch mean centering induces an $O(1/n)$ shrinkage of the KL gradient term (equivalently, a slight reduction in the effective $\beta$). This is typically negligible for large group sizes (e.g., GRPO); for strict unbiasedness while retaining variance reduction, use a leave-one-out mean.

When to Choose Which Approach?

| Dimension | KL as Loss | KL as Reward |

|---|---|---|

| KL gradient form | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ (low-var choice) | $\rho s_\theta k_1$ |

| Coupling w/ Advantage | Fully decoupled | Coupled through shaped reward |

| KL centering | None (absolute penalty) | Yes ($\text{KL} - \text{mean}(\text{KL})$) |

| Credit assignment | Local, per-token | May have temporal backprop (impl-dependent) |

| Suitable for | More controllable KL, less critic-dependent | More global KL constraint with planning capability |

Practical recommendations:

-

If you want KL constraint to be “corrective” — allowing the agent to explore but locally correcting its behavior, while keeping KL pressure more controllable and less dependent on critic quality — choose KL as Loss, using $\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ or $\rho k_3$. For on-policy scenarios, if you prefer not to explicitly construct $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$, directly using $k_2$ is simpler and less error-prone.

-

If you want KL constraint to be “preventive” — having the agent avoid high-KL regions from the outset, accepting that KL is modulated by the baseline — choose KL as Reward, using $k_1$.

Based on the above conclusions about “value unbiasedness vs. gradient correctness” and “differences between Loss and Reward implementations”, we now proceed to the quick reference guide and common pitfalls that can be directly applied to code.

Practical Guide and Common Pitfalls

Quick Reference for the Three Estimator Definitions

$$ k_1 = \log \frac{q_\theta}{p}, \quad k_2 = \frac{1}{2}\left(\log \frac{p}{q_\theta}\right)^2, \quad k_3 = \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta} $$

Value Estimation Properties

| Estimator | Unbiased for reverse KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q_\theta \| p)$ value? | Variance |

|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | ✓ | High (can be negative) |

| $k_2$ | ✗ (but bias is minimal) | Low |

| $k_3$ | ✓ | Low |

Quick Reference Tables

On-Policy Optimization of Reverse KL (Loss)

| Loss Form | Pros | Cons | Rec. |

|---|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | — | Gradient expectation is zero, completely ineffective | ✗✗ |

| $k_2$ | Correct gradient (reverse KL), low variance, simplest implementation | Value biased (but bias is minimal) | ✓✓ |

| $k_3$ | — | Gradient corresponds to forward KL, wrong direction | ✗✗ |

| $\frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)} k_3$ | Correct gradient (reverse KL), low variance, value unbiased | Requires explicit $\rho$ construction, slightly complex | ✓ |

Note: $k_2$ and $\frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)} k_3$ have identical gradients (sample-level equivalent). For on-policy, directly using $k_2$ is recommended as the simplest approach.

Off-Policy Optimization of Reverse KL (Loss)

| Loss Form | Pros | Cons | Rec. |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_1$ | Correct gradient (reverse KL), value unbiased | Higher variance | △ |

| $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_2$ | — | Gradient corresponds to f-divergence (not reverse KL) | ✗✗ |

| $\text{sg}\left(\frac{q_\theta}{\mu}\right) k_2$ | Correct gradient (reverse KL), low variance | Value biased (but bias is minimal) | ✓✓ |

| $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_3$ | Correct gradient (reverse KL), low variance, value unbiased | — | ✓✓ |

Note: $\text{sg}\left(\frac{q_\theta}{\mu}\right) k_2$ and $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_3$ have identical gradients (sample-level equivalent). Both are recommended choices.

KL as Reward Penalty (stop-gradient shaped reward)

| Estimator | Pros | Cons | Rec. |

|---|---|---|---|

| $k_1$ | Value unbiased, induced policy gradient unbiased | Higher variance | ✓✓ |

| $k_2$ | Value biased | Induced policy gradient biased | ✗✗ |

| $k_3$ | Value unbiased, low variance | Induced policy gradient biased, bias term is $-\nabla D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p\|q)$, may cause training collapse | ✗✗ |

Note: For reward penalty scenarios, only $k_1$ is the correct choice. Although $k_3$ is value-unbiased with lower variance, it causes biased policy gradients, with training collapse observed in experiments.

Legend

- ✓✓: Strongly recommended, theoretically correct with good practical performance

- ✓: Recommended, theoretically correct but slightly more complex or has minor drawbacks

- △: Usable but with caution, has issues like high variance

- ✗✗: Do not use, theoretically incorrect or causes training failure

Common Pitfalls

- Using $k_1 = \log \frac{q_\theta}{p}$ directly as Loss (on-policy): Gradient expectation is zero, completely ineffective.

- Using $k_3 = \frac{p}{q_\theta} - 1 - \log \frac{p}{q_\theta}$ as Loss to optimize reverse KL (on-policy): Its gradient corresponds to forward KL $D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p \| q_\theta)$, wrong direction.

- Using $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_2$ (importance weight not detached) off-policy: Gradient corresponds to f-divergence, not reverse KL.

- Using $k_3$ in reward penalty: Although value-unbiased, it induces a biased policy-gradient update and may lead to training collapse.

- Simply setting $\rho$ to constant 1 in on-policy: Must explicitly construct $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)}$ (or equivalently $\exp(\log q_\theta - \text{sg}(\log q_\theta))$), otherwise the score-function gradient path is lost, causing $\rho k_1$ and $\rho k_3$ to degenerate to naive forms and fail.

- Confusing “value unbiasedness” with “gradient correctness”: $k_3$ is value-unbiased for reverse KL, but when used as a reward penalty, the induced policy gradient is biased; both dimensions must be considered when choosing an estimator.

Summary

This post systematically analyzes the three KL estimators $k_1, k_2, k_3$ around three core questions: who to sample from, how to use it, and what to estimate.

Core takeaway: Value unbiasedness ≠ Gradient correctness. When choosing an estimator, you must consider both “whose value is being estimated” and “which optimization objective the gradient corresponds to”.

Key content:

- Value estimation: $k_1$ and $k_3$ are unbiased for reverse KL value, and $k_3$ also has low variance.

- Gradients when used as Loss: Use $k_2$ or $\frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(q_\theta)} k_3$ for on-policy; use $\frac{q_\theta}{\mu} k_3$ or $\text{sg}\left(\frac{q_\theta}{\mu}\right) k_2$ for off-policy.

- As a reward penalty: Only use $k_1$, because $k_3$ causes biased policy gradients.

- Relationship between Loss and Reward implementations:

- Sample-level equivalence: When Loss uses low-variance implementation ($\text{sg}(\rho) k_2$ or $\rho k_3$) and Reward uses $k_1$, their KL gradient terms are the same random variable $\rho s_\theta k_1$ — not only equal in expectation, but also identical in variance.

- Overall semantic differences: In the Loss approach, KL is an independent regularization term, completely decoupled from advantage, unaffected by critic quality; in the Reward approach, KL enters advantage computation through shaped reward and is processed and modulated by the baseline.

- Credit assignment differences: The Loss approach’s KL gradient is local (per-token); the Reward approach’s KL penalty may propagate through returns to affect earlier decisions.

- Unified $\rho$ framework: This post introduces $\rho = \frac{q_\theta}{\text{sg}(\mu)}$ to treat on-policy and off-policy settings within a single framework. The key insight is that routing the sampling distribution’s $\theta$-dependence through the $\rho$ gradient path makes expect-then-differentiate and differentiate-then-expect coincide under $\mathbb{E}_\mu[\cdot]$. In on-policy settings, $\rho \equiv 1$ but $\nabla_\theta \rho = s_\theta \neq 0$, which explains why directly backpropagating through $k_1$ or $k_3$ fails, while $k_2$ works as a special case.

References

-

Dibya Ghosh. “KL Divergence for Machine Learning”. https://dibyaghosh.com/blog/probability/kldivergence

-

John Schulman. “Approximating KL Divergence”. https://joschu.net/blog/kl-approx.html

-

Verl Documentation. “Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)”. https://verl.readthedocs.io/en/latest/algo/ppo.html

-

初七123334. RLHF/RLVR 训练中的 KL 近似方法浅析(k1 / k2 / k3). https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/1966872846212010437

-

Kezhao Liu, Jason Klein Liu, Mingtao Chen, Yiming Liu. “Rethinking KL Regularization in RLHF: From Value Estimation to Gradient Optimization”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.01555

-

Yifan Zhang, Yiping Ji, Gavin Brown, et al. “On the Design of KL-Regularized Policy Gradient Algorithms for LLM Reasoning”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17508

-

Vedant Shah, Johan Obando-Ceron, Vineet Jain, Brian Bartoldson, Bhavya Kailkhura, Sarthak Mittal, Glen Berseth, Pablo Samuel Castro. “A Comedy of Estimators: On KL Regularization in RL Training of LLMs”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.21852

@misc{WangZhang2025KLEstimators,

author = {Wang, Xihuai and Zhang, Shao},

title = {Understanding KL Divergence Estimators in RL: From Value Approximation to Gradient Estimation},

year = {2025},

month = dec,

day = {01},

url = {https://xihuai18.github.io/reinforcement-learning/2025/12/01/kl-estimators-en.html}

}